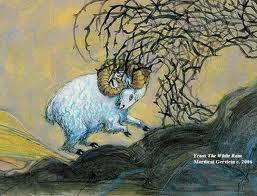

Genesis 22, also known as the Testing of Abraham, gives us great foreshadowing of Jesus in the obedient son Isaac. Although there is a point where Abraham’s “only son” is spared and God the Father’s only begotten Son is not, the foreshadowing of Jesus continues by shifting to the ram caught in the thicket. The ram becomes the substitute sacrifice in place of Issac, just as Jesus pays the price for our sins. In this pageant of sacrifice Isaac and the ram together tell the full and puzzling story.

Genesis 22, also known as the Testing of Abraham, gives us great foreshadowing of Jesus in the obedient son Isaac. Although there is a point where Abraham’s “only son” is spared and God the Father’s only begotten Son is not, the foreshadowing of Jesus continues by shifting to the ram caught in the thicket. The ram becomes the substitute sacrifice in place of Issac, just as Jesus pays the price for our sins. In this pageant of sacrifice Isaac and the ram together tell the full and puzzling story.

It is at first perplexing to view the ram of Genesis 22:13 this way because as sacrificial replacement the ram is typologically Jesus, but as snared creature the ram cannot be idiomatically construed to represent God; for God cannot be trapped in any way shape or form. In other words, while it’s easy to see in this verse Jesus as the sacrificial lamb, it seems impossible to see an all-powerful, all-knowing God as trapped, since that would mean there is another thing or person greater than God – which isn’t tenable if God truly be God.

So sometimes it appears that the ram in the thicket is we sinners stuck in our sin, and other times it appears that the replacement ram is Jesus who took the punishment for our sin upon himself. But it just doesn’t fit to pair these archetypes as simultaneously co-present the way they seem to be in the one ram and in the single verse of Genesis 22:13. It is clear that this is one thought; that the ram is both innocence captured and just atonement and that any allegorical allusion must apply both senses of the subject to the one object. And so it seemed to me that the metaphor must mean either sinners or Jesus; it should be either one or the other but not both; since the ram is one ram, the typed entity must be one entity. It just makes no sense to see God as trapped… how could God be described as trapped?! Both the lamb and the thicket are creatures; things created by God. How could a creature caught in creation be representative of the Creator? Is God caught by his own handiwork?! Of course not, so It makes no sense… until…

The answer comes inspired by a phrase in a homily of the church fathers (http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/2910.htm) which describes Adam as “cowering in the thicket of paradise”. From here we can equate the thicket with original sin, or rather the punishment for it. The thicket is mortality, which has caught all mankind by its horns; it is the just punishment for sin; it is death; it is the cross. So it is man that is caught in the thicket and is it also Jesus who is a type of all mankind; of all humanity1. When Jesus took on our human nature it came complete with everything except for sin, which means that when Jesus took on our mortality, that he could die. That is how the ram in the thicket can fully be representative of Jesus. The ram in the thicket is Jesus who became man and subjected himself to mortality and allowed himself to be crucified on the wood of the cross, which is analogous to the wood of the thicket. As one of us Jesus is “caught up” in our humanity, and as the Lamb of God Jesus is our surrogate sacrifice. The dichotomy of trapped-and-sacrificed parallels the dual nature human-and-divine in the one begotten Son of God. In order to fully and correctly apply this idiom of the Genesis 22:13 ram to God it is necessary for the person of God to be both human and divine. It takes knowledge of the persons of the Holy Trinity to solve this puzzle, or else it takes abandonment to mystery.

So now we have come to understand the ram in the thicket which is sacrificed instead of Isaac, as not only prefiguring Jesus’ sacrificial role, but also figuratively and consequently expressing Jesus’ Hypostatic Union. It is remarkable that such an image, having a meaning dogmatically ratified in 451 AD, is clearly present in the old testament in 1400 BC. But then again the church fathers seem to have known this all along and since the Holy Spirit is the author of inspired scripture, it’s fitting to be awestruck as often as clarity on holy matters strikes us.

Footnotes:

1 http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01129a.htm

“A similar line of argument is pursued in 1 Corinthians 11:8-9. More important is the theological doctrine formulated by St. Paul in Romans 5:12-21, and in 1 Corinthians 15:22-45. In the latter passage Jesus Christ is called by analogy and contrast the new or “last Adam.” This is understood in the sense that as the original Adam was the head of all mankind, the father of all according to the flesh, so also Jesus Christ was constituted chief and head of the spiritual family of the elect, and potentially of all mankind, since all are invited to partake of His salvation. Thus the first Adam is a type of the second, but while the former transmits to his progeny a legacy of death, the latter, on the contrary, becomes the vivifying principle of restored righteousness. Christ is the “last Adam” inasmuch as “there is no other name under heaven given to men, whereby we must be saved” (Acts 4:12); no other chief or father of the race is to be expected. Both the first and the second Adam occupy the position of head with regard to humanity, but whereas the first through his disobedience vitiated, as it were, in himself the stirps of the entire race, and left to his posterity an inheritance of death, sin, and misery, the other through his obedience merits for all those who become his members a new life of holiness and an everlasting reward.”